The following article is an excerpt from a presentation written by

Celeste Bolin in preparation for SxSW EDU 2020 in Austin, Texas.

At One Stone’s Idea 51 Research and Design Lab, we’re uncovering how the impulses and inherent drive of the teenage brain might actually be the key to a teen’s willingness to take the emotional and cognitive risks necessary to understand the science behind it.

About 13 years ago, at my beloved graduate school benchtop, I spent hours transferring little bits of clear liquid from one tiny test tube to another, trying to see if I could find a molecular correlation to neuronal deficiencies that may catalyze the onset of dementia and other memory-related diseases. At the time, I was about a year out from finishing my graduate research studies in neurotoxicology. From there, I ran the marathon of two post-doctoral fellowships and then a visiting assistant professorship. Then – WOOSH – I found myself in an Ironman-like sprint trying to keep up with the minds of teenagers.

Every molecule in the DNA of One Stone is coded to put student voice first. As a new coach, I learned this the hard way right off the bat. I tried to make the outcome of my efforts based on what I thought science education was – drilling skills and content and checking for comprehension. I drew on what was safe, or at least known to me, and it turned out that when students are driving their own experiences, they are resistant to passively absorbing science. My approach didn’t work. It was a big fail moment.

“The Brain” was my first successful experience learning alongside students at One Stone and effectively coaching an authentic, inquiry-driven approach to science education. During this co-learning opportunity with students, I can easily say that I learned more about the brain than perhaps any part of my education career prior. I hoped to draw on my neuroscience background and do some brushing up on what research has been done on the teen brain. What I discovered was that over the last several years there has been a flood of research that uncovers the hidden mysteries of the “teenage brain.”

One of the most important facts about development in the teenage brain is that dopamine released in response to experiences, oftentimes risky experiences, is higher – although baseline dopamine is often lower. Also, the receptivity of the dopaminergic neurons in response to this rush of this neurotransmitter associated with feelings of reward is very sensitive in the teen brain. This can translate into a couple of neuropsychology extrapolations. First, maybe everything really is kind of baseline “boring” until it is really, really exciting. Also, there’s this concept of hyperrationality – thinking in literal, concrete terms – or examining the facts of a situation but not seeing the big picture, while perhaps missing the setting or context in which those facts occur.

For example, an adolescent’s thought process about lunch in the context of hyperrationality might go something like this:

I’m hungry. I want Subway for lunch. I can drive there in 15 minutes. I’m going.

However, a few minutes into the drive, that teenager might suddenly have second thoughts:

Wait. Subway is only 15 minutes away, but it usually has a line. The wait can be as long as 10 minutes. And it’ll take me 15 minutes to get back to school. There’s no way I’ll make it back in time to find a parking spot and eat my lunch before the 45 minute lunch break is over.

However, it’s possible that a teenager has thought about the nitty gritty details of getting there and back, but to their mind, the risk is worth the reward.

Another important neurodevelopmental fact about the teenage brain is that neural networks (neurons that are firing and therefore wiring together) are still forming, and those that are not wiring together are pruning back. This pruning, or programmed death of neurons not in the network, is still active into adolescence. Also, the process of myelination, the coating of the neurons in an insulated layer of Schwann cells, is very much still taking place. So quite literally, teenage networks – whether online social networks or friend networks at school – are being deeply formed and fostered for what will be the groundwork for a lifetime of patterning, biologically, socially, emotionally, as well as cognitively.

How cool is that? A reactive brain that is highly susceptible to noticing when things are worth taking a risk and a fertile environment for laying connections to foster further growth!

What I took away from some of these insights was, Wow, I have so much to learn from these curious, capable, and fearless minds!

And what I really saw was a rare and glorious opportunity for deep empathy and helping students harness their natural strengths for self-awareness, risk-taking with brave questions, and creative innovation.

An interesting study in 2011 paid 12 to 14 year olds to play video games involving decisions about sharing money with the other players. Reciprocity meant more money for each of the players, although at a lower level. A couple interesting things came out of the study. One, when the players played selfishly, selfish parts of the brain lit up (around the temporal region) and when they shared other parts lit up. Even more novel, was that the younger adolescents were more likely to play on their own behalf, no matter what the sum of money they sought to lose or gain was. This was less likely in the older adolescents. So really, in those players’ minds, it’s all about me! I see this as such a ripe opportunity to ask the following questions: If it’s all about you, who are you? And what do you care about or maybe more importantly, what are you curious about?

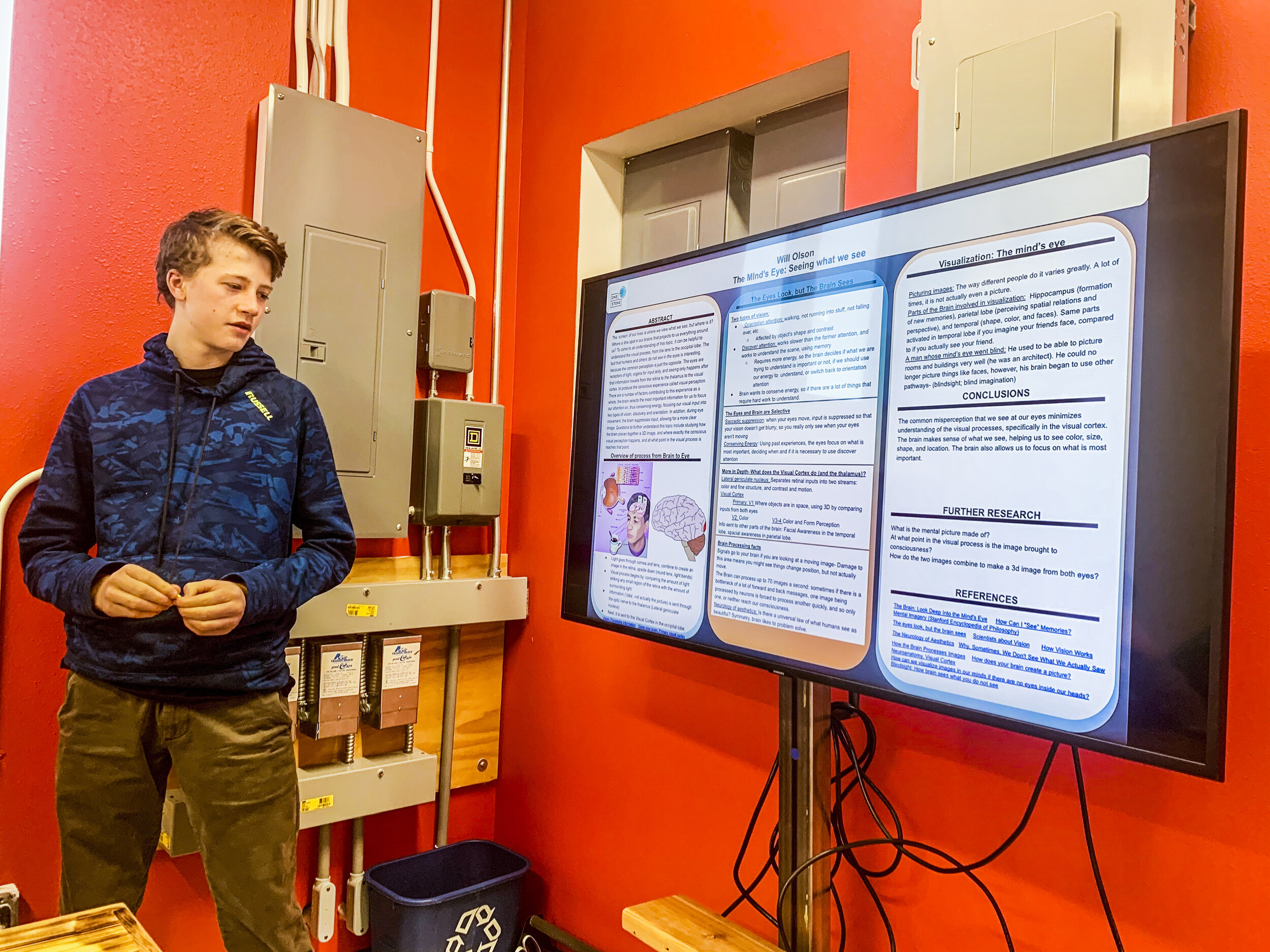

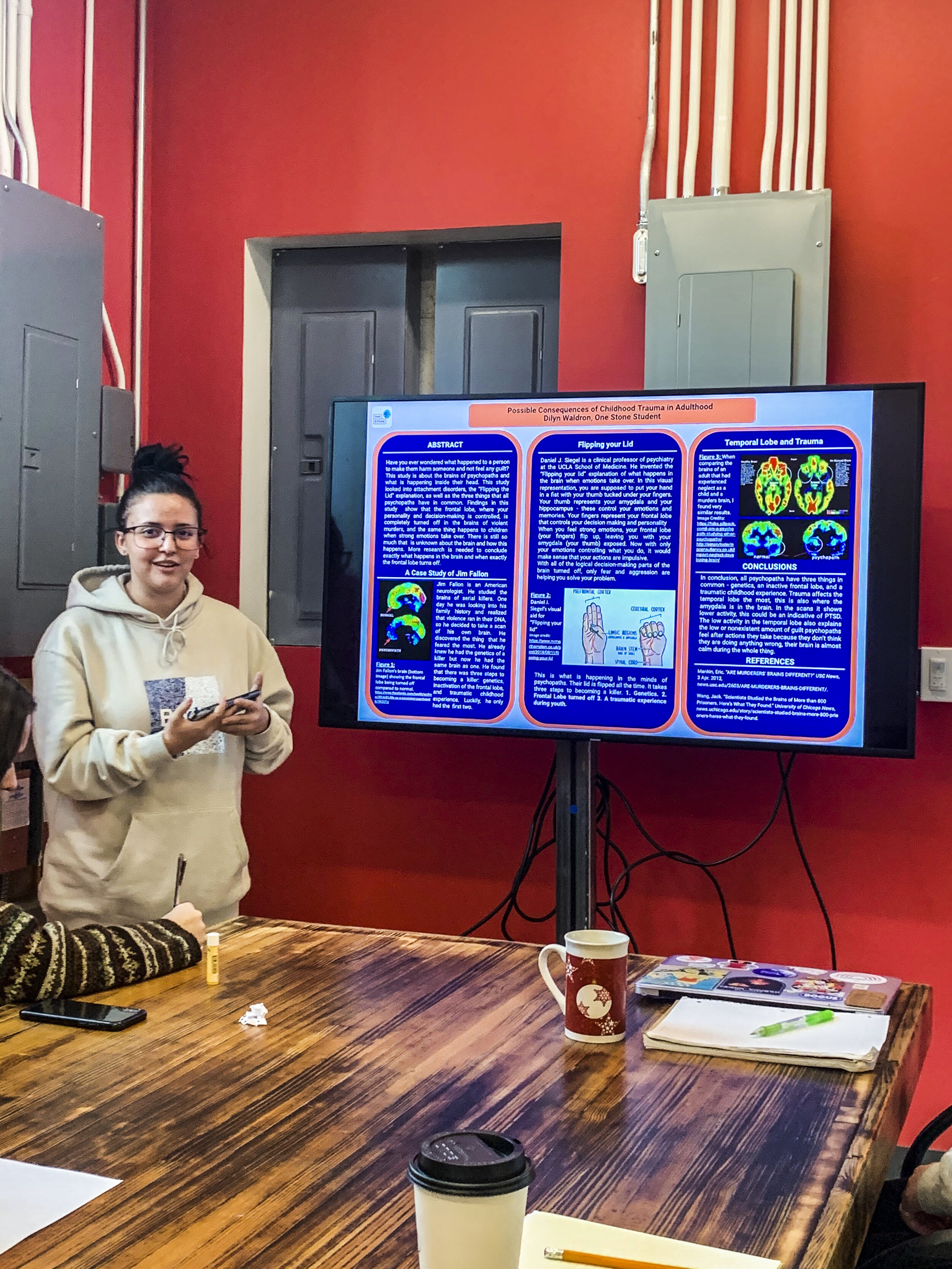

I find that when students are given full reign to dig deep and choose an aspect of the brain to study, they typically choose one of three categories: self study topics, affected family or friends study topics, or passion and interest topics. (There is overlap amongst these three.)

“‘The Brain’ made me more curious about everything to do and how the brain works in general. I also believe my ability to empathize expanded as I listened to my classmates talk about brain trauma and how it can affect an individual.”

Now, let’s look at the self-study areas that three of our students have explored.

Kayla: The Opioid Crisis

Kayla was vulnerable and found a very real drive to share what she found out when she dug deep into some of the controversies around the opioid crisis in America. Another unexpected result of this investigation was Kayla’s drive to share her opinions around opioid prescriptions and public awareness of their inappropriate use and her confidence to speak out openly about her informed opinions on this topic.

Michael: Music Therapy

Michael loves music. He was intrigued when he learned music can be an incredibly efficacious therapeutic technique for a number of movement, cognitive, and behavioral differences. He even went as far to dig deep into the history of music therapy and dating back to 1789. Beyond making it highly personal by talking to a close family friend with autism about the power of music to bring her freedom of movement and communication, he beamed with passion and pride to share it. Michael shared a video of his friend Peyton working with her therapist, which demonstrated the incredible therapeutic effect of music. As we watched this video together, everyone in the room was mesmerized. You could have heard a pin drop.

Lydia: Alcohol and Adolescence

Lydia comes from a family that has struggled with alcoholism. She is both scared and curious about alcohol and the brain, especially how a tendency toward addiction can be wired into the brain during adolescence. Lydia is a young woman with a phenomenal amount of voice who expressed that her enthusiasm investing in the topic of The Brain was primarily because she loves philosophical discussions about the metaphysical parts of the brain including dreams, emotions, our mind, and explorations as to understanding consciousness. Artistic and outspoken, Lydia does not describe herself as a “science person” but when she was asked if there was something personal and relevant to her life she might want to invest in discovering, the topic of alcoholism and adolescence was a clear choice. The power of Lydia presenting this to her peers created a dialogue that was surprisingly open and honest – with a lot of questions.

So what have we learned about how the brain works, by looking through the lens of the teenage brain?

Elbow-to-Elbow Exploration is important. Working alongside young students lays the foundation for trust and builds confidence. This encourages them to take risks and ask the hard or “scary” questions.

We should always Ask the Whys and enter the realm of the “scary.” We must ask the questions: Why do you care about this topic? Why is this important? And ultimately, we have to remember that if something scares us, it is worth investigating.

Students learn self-advocacy, empathy, and social responsibility. Studying how the brain works makes students better able to delve deep into the motivations of themselves, their families, their communities – and most importantly – find solutions to problems.

Curiosity inspires curiosity. This approach to the brain serves as a catalyst for future curiosity and increased awareness of the value of science and research.

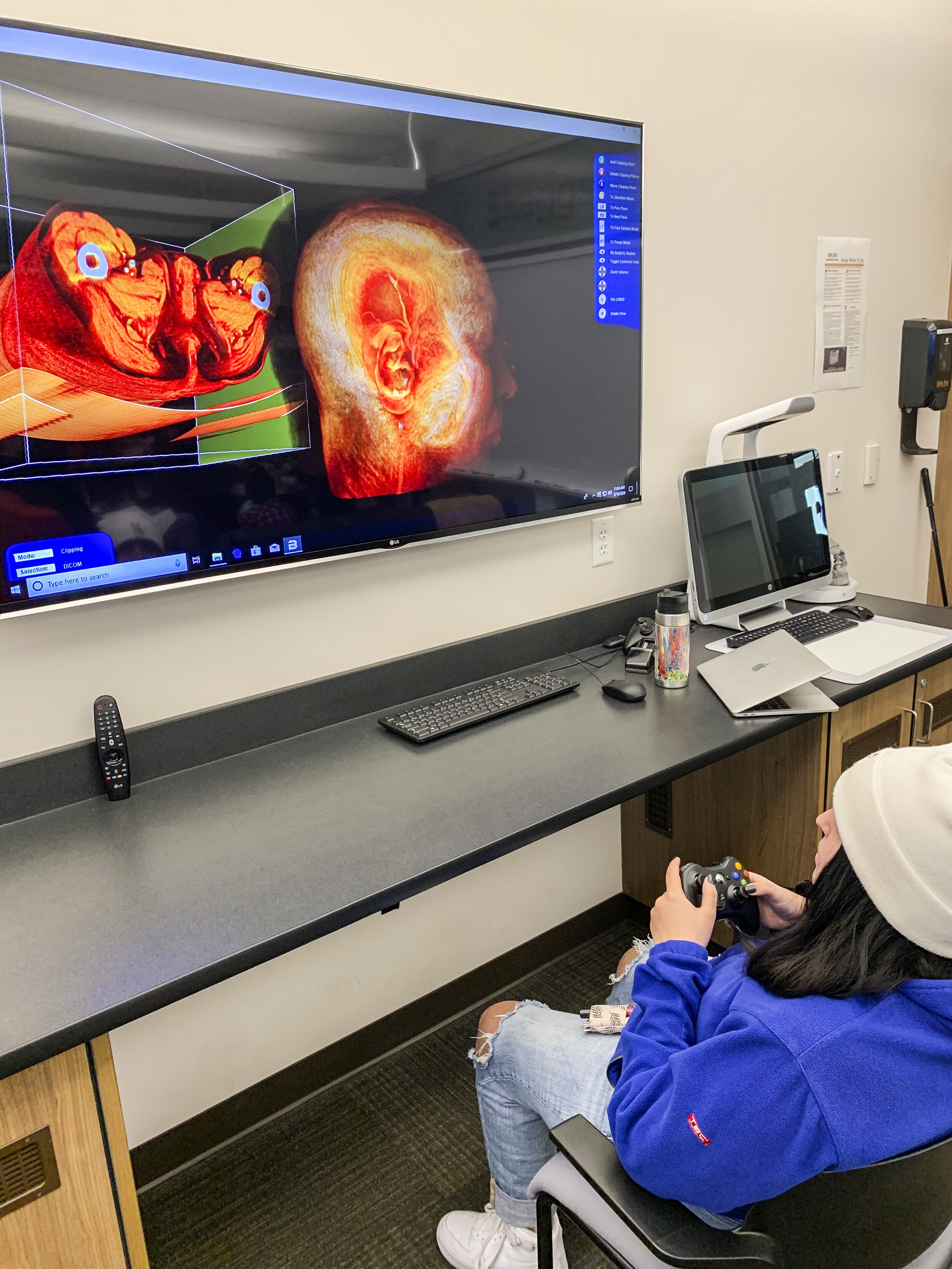

“My biggest takeaway is how my fear of learning was silenced. In the past I have struggled with disliking learning because of its end result of being forced to regurgitate it in an uncomfortable way. I have had to learn in ways that did not work for me, and to present it in the same way. When I was going through this process, I felt like I could work in a way that allowed me to learn, like when we were doing hands on learning, like brain dissections or the anatomage tables, as well as compile it in a way that made sense to me.

”

I am so grateful for the opportunity to better understand the brain through the minds of the young people I work with. The deep empathy, risk-taking, and leaps into self-awareness that they have demonstrated are truly a priceless window into the beautiful, and beautifully complicated, human mind.

Celeste Bolin is the co-director of Lab 51 and also a wellness coach at One Stone. Most recently, she was visiting assistant professor of biology at The College of Idaho where she taught Molecules to Cells, Cell Biology, Genetics and The Biology of Human Disease. Celeste has a bachelor’s degree from Whitman College, a doctorate in toxicology from The University of Montana, and has completed two postdoctoral fellowships at the Curie Institute of Paris and the Department of Biological Sciences at Boise State University. She also has a 200 YTT certificate from the Nosara Institute of Yoga.